This continues the bibliography (checklist) series with Simak and his printed English-language books. The “Main” “Works Published in Simak’s Lifetime” is the very concise core that should suffice for most (though the “Other” works in that section and the Open Road posthumous works are also significant) and the rest covers everything else, trying to balance concision and comprehensiveness in a reasonably short page.

The format is ‘Title (Data)’ where the data includes year of first book publication (with—for initial publications in the first section only—a month if known), date of first magazine publication (if any, with the format ‘Year-Month+Number of issues (if more than one)~Rate of issues (if the issues are other than monthly)’), variant titles (if any), and occasional other notes. Editions are US unless otherwise noted. Abbreviations used are general such as ‘U’nited ‘K’ingdom, ‘c’irca, ‘et c’etera, or are mostly the same as for all these checklists: ‘P’aper’B’ack, ‘T’rade ‘P’aper, ‘H’ard’C’over, ‘NO’vel, ‘N’ovell’A’, ‘N’ovelett’E’, ‘S’hort ‘S’tory, ‘exp’anded, ‘mag’azine, ‘rest’ored, ‘rev’ised, and ‘v’ariant ‘t’itle. There are also a few abbreviations specific to this checklist which are for Simak’s three major collections of independent stories: ‘Strangers’ in the Universe, The ‘Worlds’ of Clifford Simak (never to the other two with “Worlds” in the titles), and All the ‘Traps’ of Earth. In one subsection, I also refer to its books by the last part of their dates. And, as always, I’m especially indebted to the Internet Speculative Fiction Database and the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and welcome corrections.

Works Published in Simak’s Lifetime

Main

All the titles in this subsection are novels except for five collections marked [C], one connected collection marked [CC], and one novella marked [NA].

Simak’s long career had many segments. He published five stories in 1931-32 and one more in 1935 but his main career runs from 1938 until 1986 and that stretch perhaps most significantly divides in two at 1966 where he published no short fiction from 1966-68 while publishing three novels. In the first period of 28 years, he wrote something like 106 stories and 8 novels while, in the second of 20, he wrote 20 stories and 18 novels.

Phase I

- Cosmic Engineers (1950; mag 1939-02+2)

- Empire (1951; exp vt Empire: With Hellhounds of the Cosmos! 2010)1

- Time and Again (1951; mag vt Time Quarry 1950-10+2; vt First He Died 1953)

- [CC] City (1952-05; US exp w/1973 SS “Epilog” 1981, UK 1988)2

- Ring Around the Sun (1953; mag 1952-12+2)3

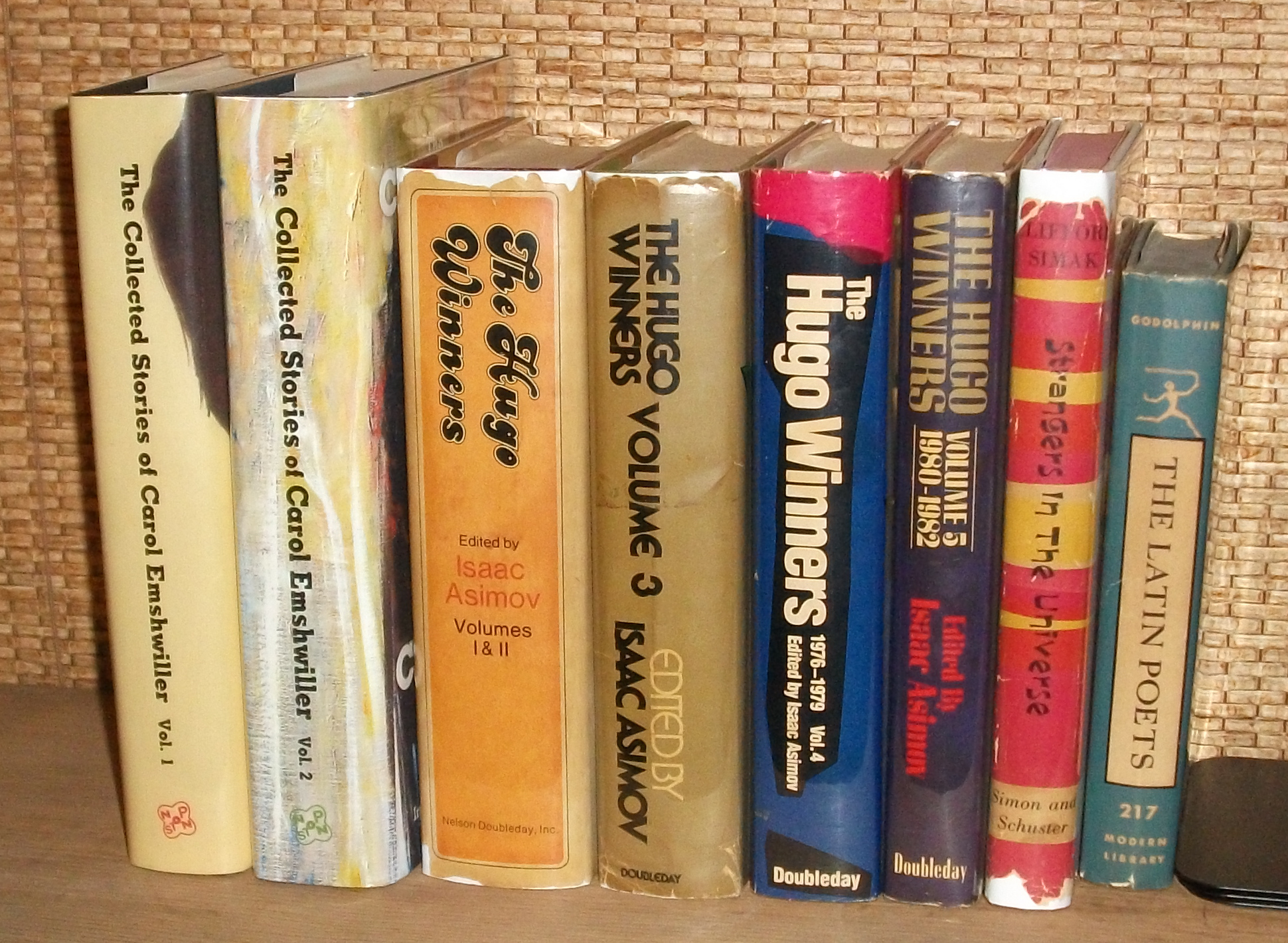

- [C] Strangers in the Universe (1956; US cut 1957; UK cut 1958)4

- [C] The Worlds of Clifford Simak (1960; UK cut vt Aliens for Neighbours 1961, further cut 1963; US split 1961 w/Other Worlds of Clifford Simak 1962)5

- [NA] The Trouble with Tycho (1961; mag 1960-10)6

- Time Is the Simplest Thing (1961-05; mag vt The Fisherman 1961-04+3)

- [C] All the Traps of Earth and Other Stories (1962-01; US cut 1963, rest 1979; UK split 1964 with The Night of the Puudly 1964)7

- They Walked Like Men (1962)

- Way Station (1963; mag vt Here Gather the Stars 1963-06+1~2)

- [C] Worlds Without End (1964-04)

- All Flesh Is Grass (1965-09)

Phase II

- The Werewolf Principle (1967)

- Why Call Them Back from Heaven? (1967)

- [C] So Bright the Vision (1968)8

- The Goblin Reservation (1968-10; mag 1968-04+1~2)

- Out of Their Minds (1970-03)

- Destiny Doll (1971; mag vt Reality Doll 1971-03)

- A Choice of Gods (1972-01)

- Cemetery World (1973-03; cut from mag 1972-11+2; rest 1983)

- Our Children’s Children (1974-01; mag 1973-05+1~2)

- Enchanted Pilgrimage (1975-05)

- Shakespeare’s Planet (1976-05)

- A Heritage of Stars (1977-06)

- Mastodonia (1978-03; UK vt Catface 1979)

- The Fellowship of the Talisman (1978-09)

- The Visitors (1980-01; mag 1979-10+2)

- Project Pope (1981-03)

- Special Deliverance (1982-02)

- Where the Evil Dwells (1982-09)

- Highway of Eternity (1986-06)

Other (Derivative/UK-only/Pamphlet)

- The Creator (1948; mag 1935; a small-press limited-edition pamphlet of a NE)

- [C] Best Science Fiction Stories of Clifford D. Simak (1967 UK; 1971 US; reprints one story from Strangers, two from Traps, three from Worlds, and adds “New Folks’ Home” (1963))

- [C] The Best of Clifford D. Simak (1975-06 UK; inexplicably titled collection reprints one story from Traps and adds two stories from 1939-40 and seven from 1959-71)

- [C] Skirmish: The Great Short Fiction of Clifford D.Simak (1977-10; reprints one story from Worlds, one from Strangers, two from City, three from Traps, and adds “The Thing in the Stone” (1970), “The Autumn Land” (1971), and “The Ghost of a Model T” (1975))

Posthumous Works

Until the final subsection, all the below are collections except for one omnibus marked [O]. While the books in the first subsection made a substantial contribution at the time in their place, none of the rest did much until the group of collections from Open Road.

1986-97: Severn House/Methuen/Mandarin Group

Simak lived to 1988 and this UK-only group includes two volumes just prior to that but the bulk of them came out after that and they belong together. (The final one also came out one year before the book in the next subsection but is grouped here for the same reason.) They are all edited and introduced by Francis Lyall and were published in HC by Severn House except 88-91. They were published in PB by Methuen/Mandarin (sometimes using only one or the other of the names) except 93 and 97. (Severn House also published 93 in TP.) They all contain 4-7 stories except 93 (9) and are 190pp or less except 88 (223), 93 (278), and 97 (250). The contents are generally collected for the first time but each reprints a story from Simak’s major antemortem US collections except 86a (0), 90 (2), and 91/93 (3). These reprint 5 of 11 from Strangers, 5 of 12 from Worlds, and just 1 of 9 from Traps.

- The Marathon Photograph and Other Stories (1986)

- Brother and Other Stories (1986)

- Off-Planet (1988)

- The Autumn Land and Other Stories (1990)

- Immigrant and Other Stories (1991)

- The Creator and Other Stories (1993)

- The Civilisation Game and Other Stories (1997)

1996: Tachyon Derivative

This limited-edition HC (though there was an SFBC version, too) reprints four longer stories (3 from Worlds, 1 from Traps) and adds four shorter ones.

- Over the River and Through the Woods (1996)

2005-06: Darkside Press’s Collected Stories

The limited-edition HC volumes from this obviously abandoned series collect only twenty-four stories.

- Eternity Lost (2005)

- Physician to the Universe (2006)

2010-2011: Wildside Press Volume

This is a TP of four public domain stories.

- Impossible Things: Four Classic Tales (2010; vt Hellhounds of the Cosmos and Other Tales from the Fourth Dimension 2011)

2013: A Gollancz SF Gateway Omnibus

A TP which reprints three unrelated novels.

- [O] Time Is the Simplest Thing / Way Station / A Choice of Gods (2013)

2015-23: Open Road’s The Complete Short Fiction of Clifford D. Simak

These TPs aren’t completely complete but do collect essentially all the stories.

- I Am Crying All Inside and Other Stories (2015)

- The Big Front Yard and Other Stories (2015)

- The Ghost of a Model T and Other Stories (2015)

- Grotto of the Dancing Deer and Other Stories (2016)

- No Life of Their Own and Other Stories (2016)

- New Folks’ Home and Other Stories (2016)

- A Death in the House and Other Stories (2016)

- Good Night, Mr. James and Other Stories (2016)

- Earth for Inspiration and Other Stories (2016)

- The Shipshape Miracle and Other Stories (2017)

- Dusty Zebra and Other Stories (2017)

- The Thing in the Stone and Other Stories (2017)

- Buckets of Diamonds and Other Stories (2023)

- Epilog and Other Stories (2023)

Other (Short Fiction Singles)

Other than The Creator and The Trouble with Tycho (discussed above), there were no books of single short Simak fictions until 2007 when the internet and the lapse of some copyrights led to a flood of trivia. Of the dozens of freely available digital tales, some of which were senselessly sold for a buck or more, some also made it into print to be sold with little more reason and for a lot more money. All of those are listed below and are available in The Complete Short Fiction. Some of the other places they can be found are also noted below.

- Hellhounds of the Cosmos (2008, a 1932 NE available at Project Gutenberg)

- Project Mastodon (2009, a 1955 NE available in Traps and at PG)

- Spacebred Generations (2009, a vt of a 1953 NE otherwise always called “Target Generation” in book form and available in Strangers)

- The Street That Wasn’t There (2011, a 1941 SS written with Carl Jacobi available at PG)

- Message from Mars (2021, a 1943 NE)

Somewhat more impressively, Armchair Fiction has its version of a Double line and has released three more Simak stories bound with works by others.

- Worlds Without End / The Lavender Vine of Death (2011; combines a Don Wilcox novella and Simak’s 1956 NA “Worlds Without End” which had appeared earlier in Worlds Without End)

- Full Cycle / It Was the Day of the Robot (2012; combines a Frank Belknap Long NO and Simak’s 1955 NE “Full Cycle” which had appeared earlier in Worlds Without End)

- The Wailing Asteroid / The World That Couldn’t Be (2014; combines a Murray Leinster NO and Simak’s 1958 NE “The World That Couldn’t Be” which had appeared earlier in Off-Planet (UK) and is available at PG)

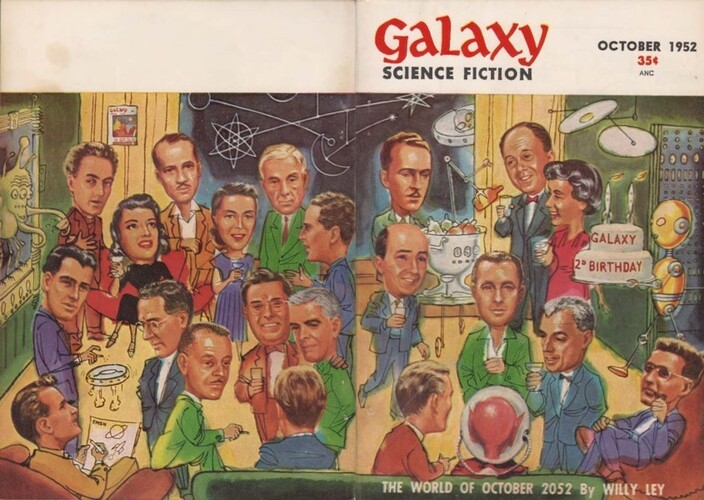

- Empire should arguably be listed in the “Other” section as it was actually written by John W. Campbell, Jr. c.1930 and then rewritten at Campbell’s request by Simak c.1940. Neither liked it and it went in the trunk until the editor of Galaxy urgently needed material for his new line of Galaxy Science Fiction Novels, so was finally published. As this was in digest magazine format it never actually appeared in book form in Simak’s lifetime. (It was never reprinted until 2009 when someone realized it was in the public domain and it’s been reprinted digitally and physically many times since. The unrelated Simak NE “Hellhounds of the Cosmos” was in the same situation from 1932 to 2008. They appeared together in the TP Empire: With Hellhounds of the Cosmos! (2010). Another TP, The Country Beyond the Curve / Empire (2015), attaches Walt Sheldon’s 1950 NA “The Country Beyond the Curve” to the Simak novel.) ↩︎

- Unusually for such bonus text, most (something like five of nine) editions of City published since the 1981 expansion stick with the original eight-story version rather than reprinting the nine-story Ace text. ↩︎

- After being published in HC, the first paperback appearance of Ring Around the Sun was in an Ace Double with L. Sprague de Camp’s Cosmic Manhunt. All other editions have published it individually. ↩︎

- The only complete editions of Strangers in the Universe are the US HCs. The US PBs and all UK editions include 7 of the 11 stories, having 4 in common and 3 unique to each, thus leaving one (“Contraption”) unavailable in either. ↩︎

- The only complete editions of The Worlds of Clifford Simak are the US HCs, though the US split PBs contain all 12 stories between them. The UK vt Aliens for Neighbours contains 9 stories in HC and 6 in PB. ↩︎

- The Trouble with Tycho originally appeared as an Ace Double with A. Bertram Chandler’s Bring Back Yesterday before being printed separately in 1976. This could also be considered an “Other” book except that it is not too far removed from novel-length and has been published in mass-market paperbacks. ↩︎

- US PBs of All the Traps of Earth had six of the nine stories until the Avon editions beginning in 1979 restored the three cut stories. The UK editions are split into a book with the original title containing four stories and The Night of the Puudly (which retitles “Good Night, Mr. James” and uses it as the title story) containing the other five. ↩︎

- So Bright the Vision is a four-story collection originally published with Jeff Sutton’s The Man Who Saw Tomorrow before being printed separately in 1976. ↩︎