This week’s large birthday gang (which could have been still larger) brings us a couple of big-canvas super-science tales, a quietly hard SF tale much closer to home, a social satire, and a powerful ghost story of the recent past.

An unusual thing about this week’s gang is that the majority are still able to celebrate their birthdays. And apologies to Linda Nagata and her fans for being a little late with hers.

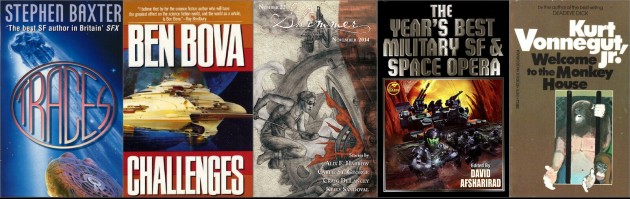

Stephen Baxter (1957-11-13)

“Something for Nothing” (Interzone #23, Spring 1988)

A nameless narrator, Harris the astronaut, and George the physicist are aboard a nuclear pulse rocket and have just caught up to the alien craft they’ve been chasing since it zipped nearby (shades of ‘Oumuamua). When they discover that the alien designers may have been attempting to send their DNA-equivalent to the site of the Big Bang/Big Crunch on a multi-billion year journey, the materialistic astronaut who wants to cut up the ship for fun and profit and the idealistic physicist who wants to respect the aliens’ intentions have a terminal disagreement. This evokes big thoughts, wide space, and deep time mediated by small interpersonal conflict rather than overwrought romanticism and stands closer to the front than the back in the long line of “guys in space solve a problem with a clever twist” and smaller line of tales such as Asimov’s “The Billiard Ball” on “unusual ways to kill a man.”

Ben Bova (1932-11-08/2020-11-29)

“To Touch a Star” (The Universe, 1987)

Aleyn has been betrayed by his best friend Selwyn and exiled from his world, time, and one true love, Noura. His exile takes the form of a one-man mission to study a star a thousand years’ journey away from our own star which has become unstable and will destroy civilization in a few thousand years. When he arrives, he learns that “that’s no star. It’s a Dyson sphere!” Actually, it’s a two hundred million year-old Dyson sphere which, when he gets inside, he learns barely contains an old, angry, unstable star… and an ancient and powerful guardian who refuses to let him leave as his ship’s heat shield begins to fail.

This, alas, suffers a little from overwrought romanticism or at least a misplaced devotion to its characters (on- and off-stage) and their issues but it’s not too badly done in that regard. Also, I have no idea how they could be looking for a specific sort of star and mistake a Dyson sphere for it, yet have just that sort of star in that Dyson sphere. But, other than that, it’s pretty well done in that regard. The discovery, adventure, and goshwowsensawunda is all present to a high degree and its emphasis on the will to survive for the individual and the species is excellent.

(P. S.: This shares the setting of “The Last Decision” but is perfectly self-sufficient.)

Alix E. Harrow (1989-11-09)

“A Whisper in the Weld” (Shimmer #22, November 2014)

Adapted from a review on my old site from 2015-05-22

I was so impressed with “The Animal Women” (which turns out to be Harrow’s second story) that I went looking for more and found her first. It shows what an opening line hook is.

Isa died in a sudden suffocation of boiling blood and iron cinder in her mouth; she returned to herself wearing a blue cotton dress stained with fresh tobacco.

We proceed to learn about the Bell family, which had moved from Kentucky to Maryland during WWII: how husband Leslie went off to fight and has been reported killed; how Isa came to build ships and die under a furnace in the story’s present of 1944; how the orphans Vesta and Effie (Persephone) strive to stay together; how Isa, as a wonderfully conceived ghost, is caught in an interplay of metaphysical forces urging her to go and personal “mule-headedness” enabling her to stay. She doesn’t want to see her children abandoned and she really doesn’t want Vesta to go to work in her place.

This has all the excellent writing, deft characterization, tangibility of time and place, and other virtues of “The Animal Women” and minimizes the one major problem of that tale. While there is a white bossman at the shipyards who is probably not a very great guy and serves as a magnet for Isa’s frustration, symbolizing the war machine and the society that isn’t always kind to its members, this is more a function of his position than his personality. The conflict is more between desires and facts and, while Isa may not fight all facts, she fights as much as she can.

I still think the two stories demonstrate a problem with, for example, the villains being too flawed and the heroes not flawed enough and the social motifs sometimes detracting from both the individuality and universality of the characters which are otherwise excellent, but Harrow is definitely a writer to watch.

Linda Nagata (1960-11-07)

“Codename: Delphi” (Lightspeed #47, April 2014)

Adapted from a review on my old site from 2015-06-09.

A woman is in a control center in a future military, physically safe but mentally responsible for the lives of many people in her charge who are emphatically not physically safe. This simply covers one of her shifts and, while the story allows the character to occasionally have a second to grab a sip of water from a nearby bottle or the like, neither story nor character deviate from their mission for more than those seconds in the cracks between wall-to-wall tension.

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr. (1922-11-11/2007-04-11)

“Harrison Bergeron” (F&SF, October 1961)

Liberty, equality, fraternity! But what if liberty and equality are antithetical? In a world in which a Handicapper-General makes sure that any beautiful people are made ugly, any strong people are made weak, any skilled people are made incompetent, so that all will be equal, what place is there for a handsome giant and a beautiful ballerina? And if they try to make a place, what sort of place would that be?

An interesting, concise tale (which may have inspired Ellison’s variant, “‘Repent, Harlequin!’ Said the Ticktockman”) that offers no easy answers.